It’s extremely important to know what differentiates you from your peers. Emphasis on “peers”, as opposed to other writers in general. Being able to say “I write dark fantasy.” is not enough. At best, it differentiates you from the other genres out there, and at least the word “dark” narrows it down a little, but your voice is the magic way your words come together, in a way no one else could perfectly imitate.

First, let’s have a quick, but more thorough definition of the term “Voice”.

What Is a Writer’s Voice?

Image here

A voice is the most noticeable characteristics of a writer’s style. In my personal opinion, it’s differentiated from style by being about the highlights within it. Every writer has a style, or else they would only be able to transcribe prose rather than write it, but it’s the voice itself that creates a real impression. Every writer can compose a decent scene, but some will emphasize punchy, non-realistic dialogue, while others build the setting in every paragraph, and others outline unseen background details through telling.

There are likely infinite possible impressions a writer can make with their work, and thus an infinite number of unique voices. David Foster Wallace and Chuck Palahnuik are my best two examples of how completely different writing voices can be, one verbose and grandiloquent, the other blunt and irreverently simplistic.

What Isn’t a Writer’s Voice?

Image here

You likely have personal preferences and rules on what you think good writing should be like. Maybe you don’t believe in ever ending or starting a scene with dialogue. Maybe you believe in the use of repeated narrative elements. Maybe you’re staunchly against telling, even as foreshadowing. Maybe you’re against going too long with back and forth dialogue without some description to fill the space. There are all sorts of preferences you can have, but the voice is more about how those preferences manifest themselves in your work.

Sure, maybe you don’t believe in ending a scene with dialogue. So what do you do instead, for a dialogue heavy scene? Or do you even have those? Maybe you write your story in a way that works around these issues. Whatever you actually do based on your rules, that’s the voice aspect of your writing.

Time and Nurturing

Image here

If you think “My voice is just kind of normal, I guess.” then you may not have nurtured your voice enough yet, so it doesn’t stand out to you. For instance, my writer’s voice is extremely present in my daily life. Every single thing I read, I subtly interpret within the style I would prefer to write it. I’ll be reading a passage or hearing a line of dialogue from a show and the words won’t reach me exactly as they were written, but rather with some tinkering from the voice in my head that insists on how certain phrases or sentences should sound.

If you are a beginning writer and want to nurture your voice, the one thing I can’t recommend enough is going to a workshop. The amazing contrast that your writing makes compared to others’ becomes obvious once a group reads and critiques different works back to back over an hour or so. You’ll also hear what people specifically like about your work, which helps you pinpoint the things that stand out in a positive way.

To be perfectly honest, you’ll also hear things at a workshop that make you think “Wow, I would never write something like that.” whether because it seems awful or because it just doesn’t gel with your interests at all. Note that I’m not talking about genres or topics, but style. I was once at a workshop where someone had their work read, and I was totally put off by how resistant the work was toward explaining anything to the reader. Was it objectively bad? That’s really hard to say, but I knew that I myself wouldn’t write something that way.

That is why I recommend workshops, but in truth simple reading helps as well. What matters is discovering your preferences in the vast sea of written expression. That’s why I see developing a voice like fumbling through a maze. Just like so many other things in life that we have to discover about ourselves, we have to hit a lot of dead ends and wrong turns before we find the path that works.

Reading Versus Writing

Image here

A common misstep I’ve seen is attempting to write in a style that matches what you like to read. While it’s certainly possible that you’ll love to read the exact same things you love to write, I’ve found that this isn’t true at all for me. I enjoy sci-fi elements in stories of varied genres, and it just so happens that I have an idea I’m writing that is predominantly soft sci-fi and dystopian. That shouldn’t stand to reason that I read tons of dystopias or sci-fi works, and am well-versed in the genre.

Quite the contrary, in fact! I don’t like to get too tired of the very genre I’m immersed in, believe it or not.

This is a point that I feel has to be made, because so many people are obsessed with that line from Stephen King’s On Writing: “Read a lot and write a lot.” But that doesn’t mean you have to force yourself to write the kind of things you love to read, or read the kind of things you love to write. My reading and entertainment preferences, in general, are very broad. I read Junji Ito, watch Daredevil, play pretentious art games, and read old works with some sort of interesting history behind them. I try to absorb art in every form possible that interests me personally, and all of it affects my writing.

There’s something weirdly incestuous about the prospect that we must write exactly like the things we read, rather than taking a broad inspiration from diverse sources. I think it’s partly born from the marketing guru, self publishing age, where people approach certain writing genres and styles like a market that must be analyzed to find a new niche. It’s just weird and kind of the opposite of artistry.

Now, if your writing interests perfectly match your reading and entertainment interests, that’s…quite something. I can’t decide if it’s better or worse, but my two points are:

1: It is normal and acceptable to branch in many different directions, whether as a writer compared to what you read, or as a reader compared to what you write.

2: Forcing oneself to do the opposite may hinder one’s ability to find their writer’s voice. Especially if their style doesn’t match any of their genre contemporaries.

But this has gone far enough with the definitions and declarations. Let’s get practical.

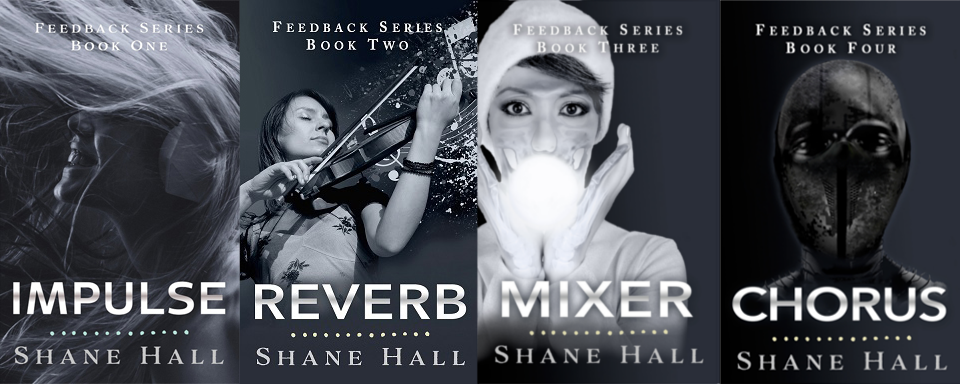

An Exercise

Image here

Here’s an idea that I’ve found particularly helpful, which I will now steal from some old college professors of mine.

Watch a scene in a movie that you have never watched. If it’s a movie you have heard of and you know the general premise, that will work best. Go on Youtube or wherever, and watch the scene. Study it carefully to try and get the context of it and what it’s trying to achieve.

Watch it one more time if you want, but when you’re ready: write that scene in prose. Pretend that scene is an original idea that you want to put to print. For bonus points, have another writer friend (or two, or three, etc.) do this along with you. When you see the different ways individuals can depict a scene, emphasizing certain details while minimizing others, you’ll get a true sense of what kind of voice you have.

My Writer’s Voice

In order to help solidify this concept, I think it would help if I attempted to define my own writer’s voice, as much as I can. Perhaps this will help people start to think of their own voice by seeing similarities or differences with my own.

1: I used to call myself a minimalist, but I no longer believe that I am one. My writing works with hard wordcount limits, which force me to be brief in certain ways, but I do not constantly strive to use the minimum amount of words.

2: I like to have my characters’ strengths shine clearly, and their weaknesses sneak up on themselves and other characters (and consequently the reader). Terry is an exception to this, for anyone reading Feedback.

3: I tend to like starting and ending scenes with either imagery or a unique concept.

4: When frequently changing character perspective through short scenes, I will be more likely to start and end on dialogue.

5: I never have characters say something, and then give them an attribution that doesn’t fit speech. Example: “You don’t look great,” he smiled. You can’t smile words. Don’t mistake this for “You don’t look great.” He smiled. With a period instead of a comma, they become separate events that still happen in rapid succession.

6: I generally prefer “said” to any other dialogue verb, although I will mix it up just a little. For instance, I tend to accept any verbs that deal with the throat to be acceptable for dialogue attribution. This includes such wackiness as gargled, choked, wheezed, etc.

I could come up with a lot more, but I think that’s enough to get someone thinking. If you are a beginning or aspiring writer and still aren’t sure about your voice, feel free to contact me or post a comment. I like to help writers.

Thanks for reading! If you liked this post and want to get immediate updates when I post another, sign up for my blog updates!

If you’re interested in reading my fiction, click here, and please check the box if you’d like updates from me on new books and other cool stuff.