“As with most of the future worlds in science fiction, you are not talking about the future. You are talking about the present. You are using the future as a way of giving a bit of room to move.”

-Alan Moore

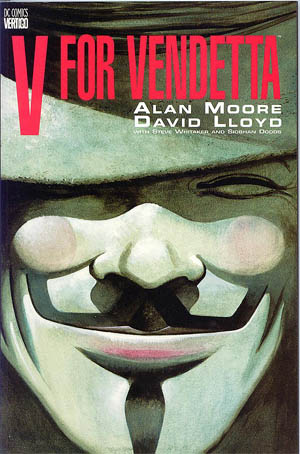

Recently, I got to thinking about my influences, particularly for Feedback, but also for my general writing interests and taste. When I try to think of one single work that influenced my writing more than any other, I keep coming back to V for Vendetta. This post should be a treat for anyone who loves V.

Take note that I’ll be talking about the film and the original graphic novel more or less interchangeably. I recognize their differences, but I won’t be discussing them here (but maybe soon!).

Where it Started

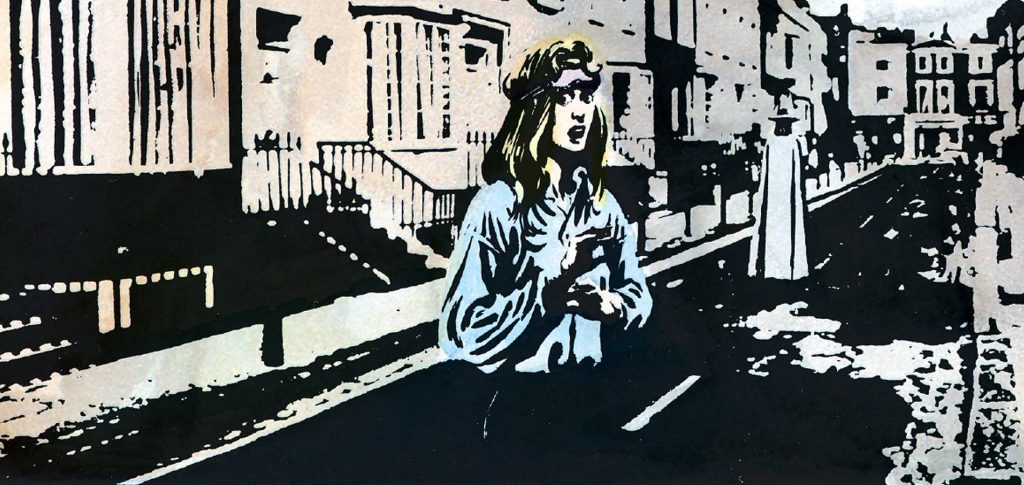

First published through the 1980s, V for Vendetta was a graphic novel telling the story of V: a masked vigilante seeking to uproot the government through methods both subtle and explosive, and Evey: a complacent young woman who finds herself forced to hide in V’s compound for one year, until the conclusion of V’s plans. Though V is the true acting force in the narrative, Evey is the protagonist, who learns the importance of V’s actions and takes a more active stand against the fascist establishment over time.

I’m not British, so I don’t know the history of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 very well. What I do know is that Guy Fawkes was one of the members in Robert Catesby’s operation to assassinate King James I and begin a popular revolt. The inciting event was to destroy the House of Lords in an explosion. However, the plan was compromised when one of the plotters under Robert Catesby sent a letter to a friend who might be harmed.

The members of the plot were eventually captured, tortured, and executed. Perhaps the most defiant was Fawkes, whose refusal to cooperate actually impressed King James. Nonetheless, this only made him a symbol of violent dissent, and November 5th, the day of the plot, became a holiday where British commoners lit fireworks, burned effigies, and wore masks caricaturing Fawkes’ snide expression and sharp facial hair.

Image here

It’s a bit of a bizarre, morbid concept when I look at it from across the pond. Sort of like Americans wearing their underwear on the outside and flying toy planes around to celebrate the Underwear Bomber’s failure.

But the Gunpowder Plot was not terrorism. It was a violent act meant to save and support one’s nation, not to spread fear and chaos in a foreign one. Through V’s actions behind this mask, he made it possible for people to see the context behind Fawkes’ actions, and better yet, to sympathize and realize that those same motivations were relevant to them, hundreds of years later. There are times when revolt is justified, and while it should be critiqued and questioned, it should not be mocked annually like a joke. Such attitudes could easily grow into a content acceptance of all the government does.

V for Vendetta is a prime example of art informing life. Today the Guy Fawkes mask is seen as a symbol of public revolt and protest. Just like at the end of the story, people go from donning the masks jokingly on a designated day to wearing it when they stand together in the streets. V does not fight against his powerful enemies solely through speed and strength, but by reclaiming a symbol. As V says in the film “Ideas are bulletproof.”

The history of the work and its real-life ties to culture today, particularly freedom-focused internet subcultures, could make this post far longer than I want it to be. Hell, we even owe the term “Guy” for any male person to the history that V trades in. For now, let’s talk about why I love V outside of all its intertext and influence. To be short: let me selfishly explain how it influenced me.

World Building

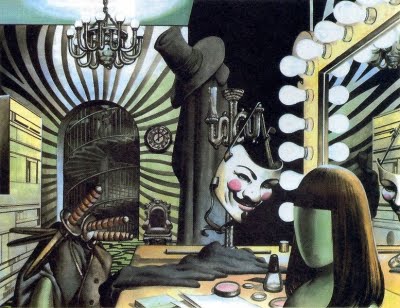

The world and the way its presented in the graphic novel is nothing short of astounding. The art style itself lays just as strong a foundation as the story. Unlike the severe, highly saturated colors of Watchmen, V’s world manages a gray, muted look. Black contributes to hard shadows and negative space, but much of the lit areas have one color blend seamlessly into another, and then another. Then there are moments with staunch singular colors for explosions or hard light. It achieves the look of a world with its beauty sucked away, although the potential for it to come back is always there.

The structure of the story itself is also impressive, as it builds the world in ways that connect back to the characters and their motivations.

For instance, Father Lilliman, the pedophile priest, instills religious rhetoric to defend the murders committed by the Norsefire, with a backwards fatalism that condemns the minorities killed and experimented on. All while building a metaphorical and literal tower where he can indulge his perversions without suspicion. It’s not the most subtle of religious commentaries, nor should it be. It leads to one of the more comedic moments in the story, when Evey plays the role of his next victim as bait for V, a full reversal of the rape attempt at the beginning of the work.

If V for Vendetta were a much simpler, lesser story then Evey wouldn’t be involved in Lilliman’s assassination. He could be interrupted from potentially raping a different underage girl by V, who then kills him. Fatalistic characters are rather difficult to write as welll. Whatever their actions, they must be assumed to be what they perceive as the only actions they could possibly take, or the actions that a higher power wishes of them. A character who chooses to prey on children, and whose philosophy dictates that whatever happens to someone is what God wished for them, is a devilishly smart pairing for an irredeemable villain. There is a similar level of resonance with all of the figureheads V takes down throughout the graphic novel and film.

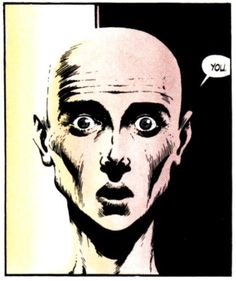

I also particularly like how V’s backstory is split into two core pieces, his own story, and the story of Valerie which he discovered while imprisoned. Rather than the story pausing in a context-free flashback, we see the story from Evey’s side when she is ‘captured’, as well as the police’s side when they research V and his history. Yet he always remains a mysterious figure. Even when vicariously seeing exactly how he was ‘made’, there is never a clear answer for who V is, and it doesn’t matter. This adds to his mystery and his dark every-man appeal. Anyone can be V. All it takes is a mask and the will to fight back.

Post-V Perspective

You’ve likely heard terms like post-modern, post-human, post-hardcore, etc. Essentially, all post means is moving ahead, doing something after what that thing has established. Post works can be a direct defiance, a commentary, or a totally benign departure from what came before.

I bring this up because when I think about my own work, I realize that it sits strongly in a newer, Post-V for Vendetta camp. Here’s a list of reasons, made by comparing the dystopia in Feedback to the one in V. I will acknowledge that there are plenty of similarities, such as a dystopian world, masked characters with extreme stealth and combat skills, and scientific experimentation leading to dangerously powerful individuals who take vengeance.

1: In Feedback, the setting is post-apocalyptic, so it is hard to even judge whether there is much point to saving what remains of humanity. Humanity has already proved that it can annihilate itself by the time Feedback begins.

2: The world of Feedback, particularly the capital city of Coltra, is extremely colorful and bright. Other senses are placated as well, like high-quality food to placate the sense of taste and smell, and soft-touch materials for the sense of touch. In this way, a world exists that provides comfort without loud or experimental audio, such as singing or music. These are seen as overblown, disruptive, and the seeds of violent uprising (something that almost no one sees as positive in Feedback’s society).

3: In Feedback, it’s not the people in power that pose the threat, or even the violent dissenters. It’s the interactions between the two, and the dangerous figureheads that can arise from either side.

4: In Feedback, there is no easy answer to why the world is the way it is (complacency among the people), and no easy solution (revolt). Set in a post-apocalyptic setting that has either forgotten or assumed much of its history, the world has few people who can look back to the pre-silence and pre-war world and say that there isn’t a connection between noise acceptance and violence. What’s more, even the protagonists who support noise tolerance aren’t brilliant historians or time travelers. There is no certainty that the supposed “good guy” side is right, and this will play a big role in future seasons, where it becomes hard to tell whether the dystopia really should change or not.

5: Unlike in V, I don’t write to deliver a clear moral or message, like “governments should fear their people”. I’d rather explore the complexity of the world that invites such ideas and the many conclusions that different people could draw. This is why I try to have as diverse a cast as possible. People from all walks of life feature in Feedback: young, old, rich, poor, downtrodden, respected, pitiful, powerful, sympathetic, psychotic, and even human and trans-human.

6: Unlike Evey, the protagonist of Feedback is a very capable, lucky, and internally rebellious free-thinking young adult. Eric needs none of the lessons that Evey learned throughout V, and fights back by himself when the world conspires against him (although a bit too late). Rather than the story teaching him a lesson directly related to the dystopia, followed by him embracing a new role, Eric makes impulsive, rebellious decisions that drag him farther into a pre-defined role that seems impossible to escape.

7: The most powerful person in the country is not Eric’s enemy and the antagonist of the story. The relationship is more complex, and Eric’s somewhat privileged background gives him direct ties to this domineering politician. However, the politician running the quiet society is not the symbol of silence. Far from it, he is a hulking brute given the right to speak up. His contradictions are worn on his sleeve, in the same way that we defend politicians for their sleaziness, their contradictions, and their lies, as if these things qualify them as good players in the game of politics.

8: Perhaps the most obvious and easily noticed: the people sneaking around in masks and killing people are not the good guys. Although, you could easily argue that V wasn’t much of a “good guy” either.

Feedback is also far longer and covers more time, giving me the luxury of exploring ideas to this level of complexity.

I should make something extremely clear: the fact that my work is post-V for Vendetta does not mean that I am challenging V’s ethics or storytelling, trying to one-up it, or anything like that. All a post work does is find somewhere new to go from the foundation of what previous works laid. I owe V for Vendetta massively. If not for it, I wouldn’t have the exciting ideas I’m currently exploring in Feedback.

I wanted to tell a dystopian story where the answers were not as black and white as V’s mask. Where the powerful, downtrodden, righteous, and corrupt all mixed together in a mass that only the most brilliant technology and cooperation could hope to sort.

Will the world of Feedback settle on a clear answer? I know that someday there will be one, but I am writing the story as I go and reaching that conclusion after a lot of exploration. If you’d like to start travelling the road I’ve been paving, and see what Eric’s world and story is like, feel free to check Feedback out.

Thanks for reading! If you have any comments on V or dystopia, please leave them below in the comments! More to come!