Hi folks. Recently, I've been wanting to recommend more specific works of fiction and their concepts, from the perspective of a writer. I've wanted to do this for a while, describing two works that I feel are intriguing in some way, and hopefully inspiring fans of one to try the other, or just for unfamiliar people to try both. If I could get a discussion regarding the two, that'd be awesome.

Today, I invite you to peruse two works of existential science fiction from different time periods: a computer game called SOMA and a novel called The Invention of Morel. I read the latter while in college, and played the former earlier this year. Both cover similar concepts, but they do so in very different ways. If you're intrigued by either, or by science fiction in general, read on.

If you want to avoid spoilers, I'll offer you my recommendations now: both the novel and game are superb examples of sci-fi, with SOMA being a brainier kind and Morel being more of an emotional journey. If you are busy or backlogged with fiction and don't expect to ever get to them, or just don't care about spoilers, I understand. In either case, I won't be spoiling the endings of either story, and you can go into either work with the knowledge below and still get a lot out of them.

First, an introduction to the two works and their premises.

The Invention of Morel

The Invention of Morel is a science fiction novel from 1940 by Aldofo Bioy Casares, a heavily influential Argentine author who affected the Hispanic speculative literature world for decades. Morel was the first work by Bioy Casares that received great attention and acclaim. In fact, Morel was described as the perfect novel by Cesares' peers: Octavio Paz and the incredible Jorge Luiz Borges.

The story of Morel is structured as a diary. A Venezuelan writer is hiding from the government, has fled to a sizable Polynesian island, and has grown accustomed to living off its land, fully memorizing most of it and living in the abandoned museum at the highest point. He is fairly confident he will never be found, and is antisocial enough to not be bothered by this. Suddenly, a group of tourists appear on the island and start living in the same museum, forcing him to flee into the lower, swampy area to avoid getting caught.

While carefully observing them from a distance, he comes to realize that they literally cannot see him, or detect him in any way. It is as if to them he does not exist. Thus, he becomes comfortable observing them, and grows to fall in 'love' (although it's more of a crazy man's infatuation if you ask me) with a young lady named Faustine. One of Faustine's friends and confidantes is the revered leader of the tourist group: a scientist named Morel.

Here's a shot of the fugitive writer and Faustine from the 1967 film adaptation.

As the writer watches the tourists, there are times where they are completely gone. Then they return and repeat the exact same actions they had performed the prior week. This, on top of being constantly ignored, leads him to question his sanity, as he also finds other bizarre things on the island, such as a duplicate sun and moon. He continues to observe them, and eventually learns the truth.

SOMA

SOMA is a horror science fiction computer game for PC, published in September of 2015 by Frictional Games, creators of popular, slightly-cerebral hide-from-the-monster horror games like Amnesia: The Dark Descent and Penumbra. SOMA was an unexpected step for Frictional, as it has less chase-horror focus, and in my opinion suffered due to it being a change in direction that the target audience wasn't expecting. It's not as face-cammable, if you'll forgive that hideous term, than Amnesia, a game popularized by videos of people playing it and screaming their heads off. Yet by the time of its release that's what most people were expecting, and instead they got a slow-burning sci-fi horror adventure with some scary monsters shoved in like an obligation.

I could go into my feelings on SOMA as a game in real depth, but I'll reserve that for another post if anyone's actually interested. I just thought that some background would help, since the circumstances of SOMA's development are so different, and so less creatively liberated, compared to Bioy Casares' novel.

SOMA tells the story of Simon, a trusting young man who has terminal brain bleeding after a car crash that was arguably his fault. He agrees to take part in a bizarre science experiment, on the hope that it could cure him. The experiment is simple: create a perfect replica of Simon's brain in digital form, which can be run through hundreds or thousands of simulation treatment methods to find the one most likely to work. Then, that method could be used on the real Simon. However, immediately after having his brain scanned he is suddenly transported to a completely different place.

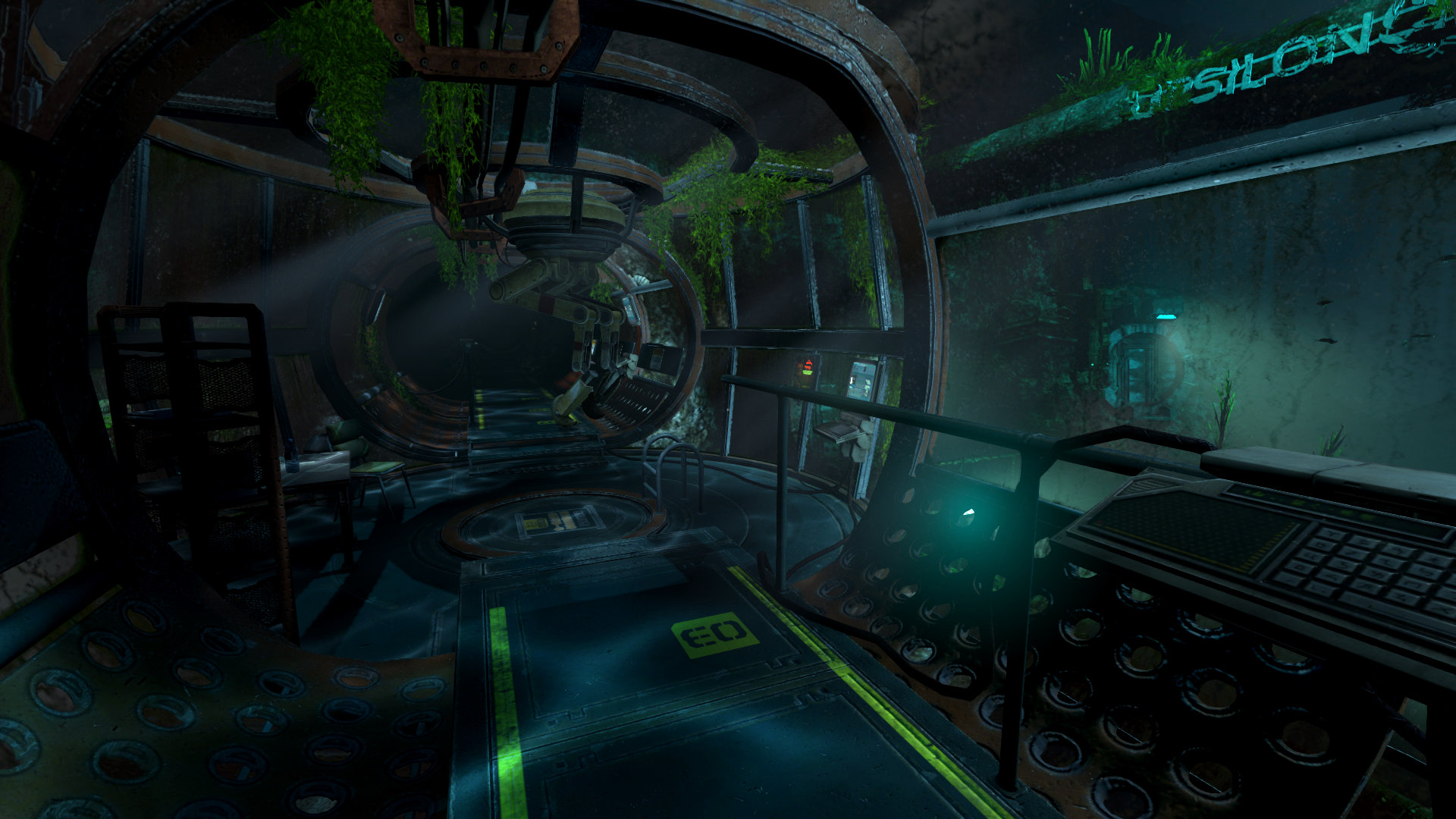

He is apparently now in the future, in a nearly-destroyed research complex at the bottom of the ocean, and the human race is almost entirely extinct after a massive comet struck the Earth. It seems like only one living, unharmed woman remains, amid a host of bizarre artificial intelligences and experiments to keep human cadavers alive.

It's up to Simon to discover what's happening, why he is now in this strange future, and what he can do to escape and save himself.

The Reveal in Morel

Eventually, the writer finds a conversation between Morel and the tourists, where Morel explains a hidden truth to them. It turns out that the island contains a machine that Morel built. It can be best described as a four-dimensional camera, and it has been recording himself and the tourists through this week-long vacation. However, the machine releases a deadly radiation while it is recording, and soon after the end of their trip they will die. However, their 'souls' have been preserved, and they will technically be immortal, re-living the same pleasant final days forever. They are not simple holograms, either. They are re-created, indestructible beings that for all we as the audience know have the true sentience of the originals. They will forever enjoy their vacation, with the finale of learning that they are immortal. Then it all starts over.

Since most of the tourists are desensitized socialites who adore Morel's scientific goals, few of them are bothered by the fact that Morel has essentially killed them. Even the writer, an outside perspective, sees the appeal of the fate Morel has bestowed onto them, and the drive to test such a revolutionary creation in secret.

That's the big reveal. It comes pretty late in the rather short novel, but there's still a very interesting ending, and a lot of cool hints leading up to it, so consider checking it out if you'd like to know more.

The Reveal in SOMA

SOMA is a far more complicated and busy story than Morel, and not always in good ways. I'll stick to the reveal of what happened to Simon, and why he's in the future, which is explained about halfway through the game. It's one of the more intriguing ideas in the game, but rest assured that things get even crazier afterward.

Simon accesses some audio files in one section of the underwater complex, including a conversation between himself and the doctor from way back in his time, soon after the brain scan. It turns out that the procedure failed, and the present-day Simon could not be cured. However, the doctor still had the perfect, digitized brain scans of Simon, who the original Simon gave consent for him to use as he saw fit.

What the present day Simon didn't realize, however, and couldn't possibly have, is that hundreds of years into the future his brain scans would be copied and used for different purposes, like trying to preserve humanity. The human population is basically extinct, and an artificial intelligence has used Simon's brain scan to try and make 'new' humans. That is what he is now.

The consciousness he now has, where he feels as if he was thrown into the future, is really a copy of the original Simon implanted into a humanoid robot body. The game does a good job explaining why Simon didn't immediately realize that he's a robot.

By the same logic, it seems possible for him to transmit his consciousness onto a special computer satellite that will be launched out into space with the rest of the available brain scans of other people. This is called the ARK, and most of Simon's journey involves trying to reach it in his robot body to be delivered into this eternal, digital heaven.

Food for Thought

I think it should be obvious how these stories have very similar subject matter. Both are about using technology to live on after death, and both bring up a crucial question: is mere continued existence the same thing as conquering death?

Reading the Invention of Morel today, as someone in a near-alien level of advanced society compared to the one Bioy Casares wrote within, makes it harder to grasp its proposals, but not impossible.

I can easily see how if I were isolated on an island, and had no intention or way of ever leaving, how I could become fixated on the mere image of a person. Especially when that image was so realistic that I did not realize it wasn't a flesh-and-blood human until being told so. But is capturing and re-living reality the same thing as preserving it?

Morel's proposed technology is fascinating, but not personally appealing to me, and here's why:

My worldview is that all that is not perceived, or especially cannot be perceived, is not worth consideration. Let's say next week I get hit by a bus and die, but I forever revive and go back in time one week without knowing it, losing all memory of that week once it restarts. Sure, it might be amazing if an outsider could perceive it, but for myself as a person, who cares? Every second of my existence will feel exactly the same. We could even all be forever reviving and reliving the same lives ad infinitum. We'd never know it, though, so to me it's hardly worth consideration.

That said, once the lethal radiation problem was ironed out, Morel's machine could make for an amazing sourcing tool for historians (barring the fact that it would have to be used without the recorded person's knowledge so as not to tamper with their natural behavior). We could know exactly how important historical figures behaved, or have the data to prove people innocent or guilty of crimes.

Then we get to SOMA's concepts of immortality and extended existence, which are for the most part presented in horrific fashion. These are ideas I could chew on for the rest of my life.

Would you be okay making the kind of decision that Simon made? Would you allow someone in the future to make copies of your consciousness? Unlike what is proposed in Morel, they're just copies. You'll be dead someday, and you won't feel anything done to the copies of yourself, so does it matter?

And yet, this is why I wanted to compare these two works. Despite all that I have to say about Morel's machine, throwing out with bravado the cry of independence: Only what I perceive matters! I am not comfortable with the idea of someone having copies of myself. Not at all.

Maybe because, ultimately, if there are infinite copies of a person's intelligence, then does their sentience withhold any moral concerns? What does it matter what you do to a person, if they're just a digital being from an infinite supply? Who cares how much you torture and warp someone if you can just toss them out and bring out a fresh replacement in the blink of an eye? Create and snuff them out, as if we are gods to their mortals?

I don't have a singular answer, so please, leave a comment if you've got a perspective on these things. Hopefully, even if you haven't experienced these works, the background and questions I pose in this post have spurred on some philosophical thinking. I'm not always one for philosophical thinking, but when it's inspired by fiction, hell yeah.

Thanks for reading. 🙂